“Arbolado para calles, imperios y paraísos: El ladrón de miel” 2023

… y Eros sacudió mis sentidos como el viento, que en los montes se abate sobre las encinas…(V, 47)

“Eros me sacudió el alma como un viento que en la montaña sacude los árboles”

Safo de Lesbos

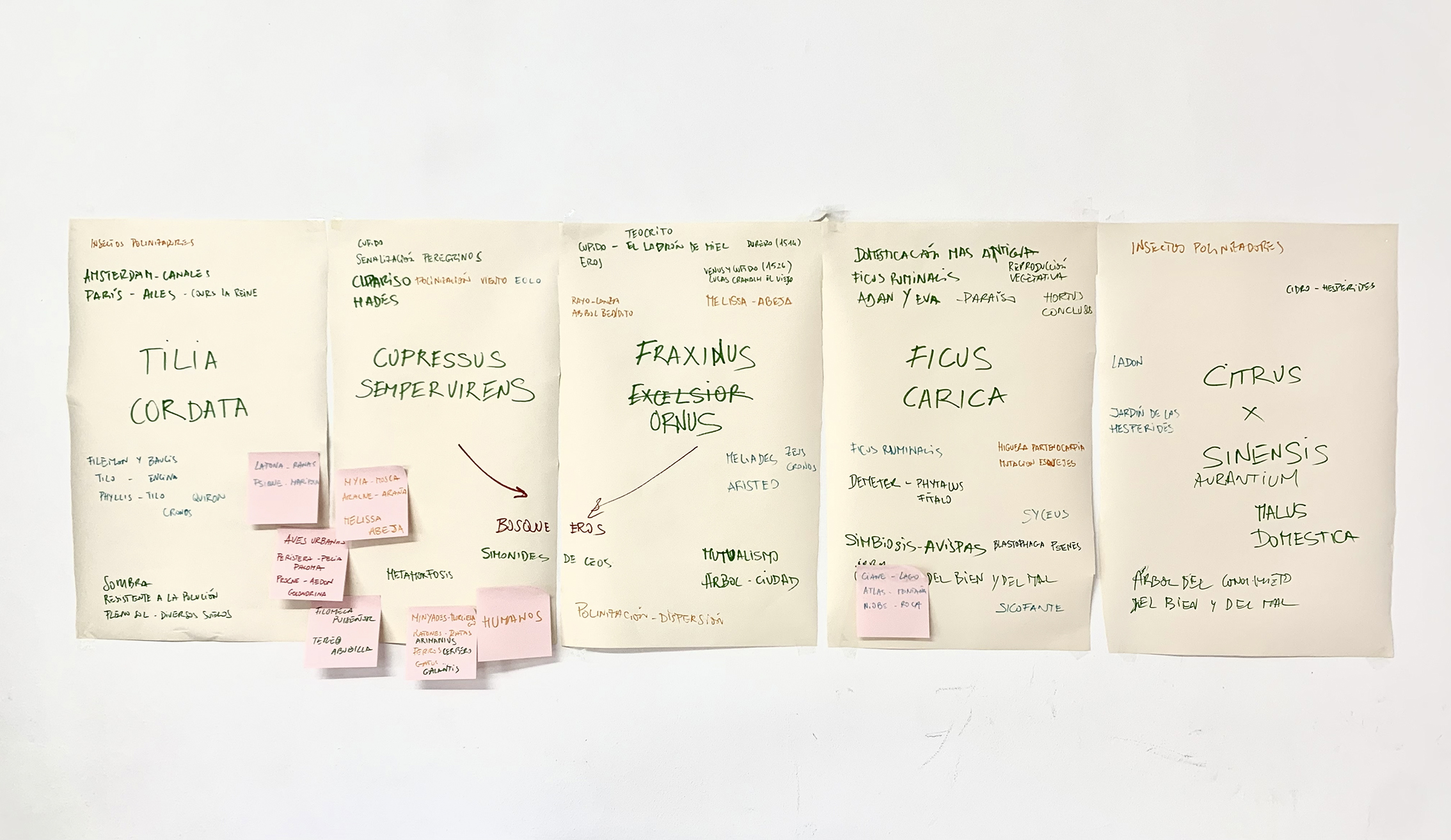

“El ladrón de miel” se enmarca en el proyecto Arbolado para calles, imperios y paraísos, una serie que plantea distintos modelos de alineaciones de árboles para el espacio público. Patrones creados a partir de un diálogo entre diferentes especies arbóreas y el contexto urbano. Pensada como “une allé romamtique”, “un paseo romántico”, traslada el programa conceptual de un jardín del renacimiento o del barroco, a una alineación urbana, recogiendo el carácter lúdico que generalmente articulaba estos jardines. “El ladrón de miel” se inspira en la figura mitológica de Eros, dios del amor, focalizando el deseo y el amor como motor y pulsión de vida. Un prototipo de esta alineación de árboles forma parte de la colección de Artium Museoa, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo del País Vasco en Vitoria Gasteiz y puede verse instalado en la plaza del museo.

El título “El ladrón de miel” hace referencia a los versos bucólicos del poeta Teócrito en los que Eros es picado por las abejas cuando se dispone a robar la miel de un panal. Llorando se queja a su madre de cómo un ser tan pequeño puede causar tanto dolor. Afrodita le reprocha que es eso precisamente lo que él hace, recordándole el sufrimiento que provoca con el divertimento de sus flechas. Esta escena fue ampliamente representada desde la antigüedad pero es a partir del renacimiento cuando su temática tomó protagonismo en la pintura. Lucas Cranach y Durero hicieron numerosas versiones.

La alineación está formada por varías especies de árboles melíferos, siendo un jardín del que las abejas pueden abastecerse de néctar para producir miel. Los árboles crean un escenario donde se representa “el ladrón de miel” evidenciando que no es solo Eros quién es el ladrón. Los árboles que la conforman son el fresno (fraxinus ornus), el ciprés (cupresus sempervires), el tilo (tilia cordata), la higuera (ficus carica), el naranjo (Citrus x sinensis) y el manzano (malus domestica). Esta alineación es la suma de relatos y mitos creados desde la antigüedad en los que los árboles han sido protagonistas. Según la narración atribuida a Simonides de Ceos, Eros construyó su arco con madera de fresno y sus flechas con madera de ciprés. Estos dos árboles parten de un bosque mitológico y articulan la alineación funcionando como vectores multidireccionales, metáfora de las flechas de Eros.

Las narraciones mitológicas generalmente son historias de amor, pasión, juegos de seducción, traición, venganza, tragedia… en muchos casos son la explicación o interpretación mitológica de la creación de muchas de las especies vegetales, animales y la formación de fenómenos naturales…

Puede trazarse un paralelismo entre estos juegos de seducción y las estrategias de polinización y reproducción de plantas y árboles. El ejemplo de la orquídea “Ophrys apifera” ilustra cómo una flor ha acabado metamorfoseando su apariencia con el cuerpo de una abeja hembra, preparada para ser polinizada mientras el macho intenta copular. Encontramos este tipo de engaños y estrategias en numerosos relatos mitológicos en los que las divinidades transforman su apariencia en animales, plantas, lluvia, nubes. Los árboles utilizan múltiples tácticas para servirse del viento, fuego, todo tipo de animales como insectos, aves, mamíferos, microorganismos, humanos,… son los recursos de los que se sirven para reproducirse y han dado forma a su evolución. En este paisaje formado por múltiples interacciones encontramos las relaciones de simbiosis, mutualismo, depredación y parasitismo que conforman el ecosistema natural.

“El ladrón de miel” traslada este paisaje mitológico al ecosistema urbano para interrogar la relación entre los árboles y la ciudad, subrayando los beneficios que estos generan y cuestionando los desequilibrios que el urbanismo actual produce. Es una metáfora que subraya nuestra actitud más cercana a la depredación y el parasitismo que a la simbiosis donde cada agente que lo compone sale beneficiado. Busca subrayar la relación entre especies para pensar un posible mutualismo entre los árboles y el espacio urbano, imagina un mutualismo árbol-ciudad en el que no seamos meros “ladrones de miel”. Esta posible relación de simbiosis entre la ciudad y el árbol engloba a todo los agentes que intervienen en el proceso.

Así como la abeja provoca la metamorfosis de la orquídea, los árboles pueden transformar la fisonomía del espacio urbano. A día de hoy, el arbolado hace habitables las ciudades siendo imprescindible en su diseño, absorbe el CO2, purifica el aire, equilibra la temperatura, es el hábitat de múltiples especies de animales aumentando la biodiversidad y globalmente es un elemento clave frente a la crisis climática.

El vínculo entre los humanos y los árboles es inseparable desde los orígenes de las civilizaciones, todas las culturas han dependido de ellos para su nacimiento y evolución, de hecho no es posible nuestra existencia sin ellos. Los inicios de la agricultura en el Creciente Fértil propició el cultivo y la reproducción de árboles frutales, lo que supuso la evolución de los poblados estacionales a los poblados permanentes.

Han sido el recurso y materia prima de las civilizaciones al igual que un vehículo hacia lo trascendental. Bosques, jardines y paraísos han funcionado como escenarios de relatos originarios. Los jardines de la antigüedad, (el «hortus conclusus» medieval), los jardines renacentistas y barrocos mantuvieron los relatos míticos como guión conceptual en su diseño. La evolución de estos espacios verdes de uso privado en su origen, fueron los parques públicos y las alineaciones arbóreas de las ciudades. La aparición en occidente de los árboles en el espacio público tal y como los podemos encontrar en la actualidad, tiene un paralelismo con el desarrollo del capitalismo y la revolución industrial.

El “ladrón de miel” funciona como un artefacto de seducción, atraviesa el atrio del museo Artium emitiendo el perfume de la floración, una fragancia que apela a todos los seres que forman el ecosistema urbano.

La obra superpone sobre la cotidianidad el plano mitológico creado por las narraciones en las que los árboles son protagonistas. Construye un guión performativo en el que estaremos rodeados por numerosos personajes y comenzaremos a interactuar con ninfas, dragones y centauros, un teatro que apela a la participación. Si los arboles nos introducen en este paisaje imaginario también los animales del espacio urbano se suman a los múltiples relatos con sus símiles mitológicos. Un perro pasando al lado del ciprés, podría ser Cancerbero protegiendo el reino de Hades, en una mariposa revoloteando podríamos ver a Psique intentando entrar al inframundo, una paloma de la plaza nos recordaría a la ninfa Peristera transformada por Eros en ave, las Míniades nocturnas serían los murciélagos y lechuzas, Aracne tejería su tela entre las flores del naranjo, un gato sería Galantis, quizás una rata buscando fruta sería Arimanius, las ranas Latona y las abejas protagonistas de “El ladrón de miel” tendrían el carácter protector de Melisa.

El ciprés siempre ha tenido connotaciones espirituales relacionadas con el inframundo, siendo consagrado al dios Hades, su porte vertical lo identifica como una conexión entre cielo y tierra, un puente simbólico hacia lo espiritual. En su lado más práctico este árbol ha sido fundamental para la construcción a lo largo de la historia. Su porte vertical lo hace visible desde la distancia por lo que los romanos solían situarlo a lo largo de las calzadas para trazar el curso de los caminos a gran distancia. Igualmente en la época de las peregrinaciones cristianas el ciprés funcionaba como señal, era un recurso visual en el paisaje que informaba a distancia sobre la posibilidad de encontrar agua, alimento u hospedaje. Según el numero de cipreses que se veían al lado de una construcción se anunciaban los servicios a los viandantes. He utilizado este recurso en la alineación al ver que la entrada principal del Artium coincide con el paso del Camino de Santiago por el cantón de San Francisco Javier. El ciprés anuncia a los “peregrinos” la presencia del Artium, abastecimiento sensorial, intelectual… dependiendo de la mirada del visitante.

En la entrada del Artium nos recibe la higuera, considerada uno de los primeros árboles domesticados por la humanidad en el Creciente Fértil. En su versión mitológica fue el regalo que Demeter, diosa de la agricultura hizo a Fítalo en agradecimiento a su hospitalidad cuando buscaba desesperadamente a su hija Perséfone raptada por Hades. Los relatos míticos de la higuera nos llevan también a la tradición judeocristiana, al paraíso del que fueron expulsados los humanos utilizando la hoja de higuera para cubrir su desnudez. A su vez, está presente en el mito fundacional de Roma, Ficus ruminalis es la higuera bajo la cual la loba amamantó a Rómulo y Remo.

Este árbol es un buen ejemplo de mutualismo entre dos especies, la morfología del higo y su polinizador han coevolucionado de modo que la higuera es exclusivamente polinizada por la avispa del higo, Blastophaga psenes.

Por otro lado la mutación denominada partenocárpia da la posibilidad de reproducir la higuera de forma vegetativa sin necesidad de polinización, siendo estas las variedades más extendidas en la actualidad.

Al entrar en el atrio percibimos el perfume de las flores de azahar, situado en el interior del Artium hace alusión al “Jardín de las Hespérides”. En uno de sus trabajos, Heracles tiene que robar las “manzanas doradas” protegidas por las ninfas Hesperides y por el dragón Ladón. Hay diferentes opiniones sobre si realmente los árboles eran manzanos o naranjos, he incluido las dos en la alineación por la climatología y porque ambas son ejemplo de especies frutales de producción industrial, como señalaría Henry Thoreau en “Manzanas silvestres”, toda una relación de especies silvestres y especies no comercializadas que tienden a desaparecer frente al uso exclusivo de determinadas frutas dentro de un mercado globalizado. Tanto la naranja como la manzana son el mejor ejemplo de la estandarización productiva de un árbol en detrimento de la biodiversidad.

Thoreau imaginaba bellas especies como la de las manzanas que se dejan en el árbol para que sean robadas por los niños que saltan el muro. Esta idea también esta presente en el “ladrón de miel” las manzanas doradas deben ser robadas pero tendrás que evitar que las Hespérides o el Dragón Ladón te atrapen. Si consigues escapar, al salir tendrás que verte con los Sicofantes, los delatores y guardianes de las higueras sagradas.

La floración del fresno fraxinus ornus es exuberante en formas y aroma, al hacerse incisiones en la corteza su savia produce una sustancia dulce y blanquecina que recibe el nombre de “maná” por su parecido a la descripción del alimento bíblico. En la cultura vasca el fresno ha tenido siempre un carácter divino por la creencia en sus cualidades protectoras frente al rayo. En la Teogonía de Hesíodo se describen a las Meliades, las ninfas del fresno, nombre que comparte raíz etimológica con “melífera” que produce miel y según el poeta Calímaco ellas tuvieron su importancia por ser precisamente las protectoras del dios del rayo, de Zeus cuando era un recién nacido y su padre Cronos lo buscaba para devorarlo. Otra versión narra que fue Melissa junto a sus hermanas lo protegieron y alimentaron con leche y miel, como castigo Cronos transformó a Melissa en un gusano pero posteriormente Zeus las convirtió en abeja.

Mientras Cronos buscaba a Zeus se encontró con la oceánide Filira, para seducirla se transformó en caballo y de esta unión nació el centauro Quirón, figura del maestro sanador. Filira horrorizada por la criatura que había dado a luz pidió ser transformada en un árbol, el tilo. Tilia cordata, es uno de los árboles más utilizados en el espacio público a lo largo de la historia debido la sombra que produce, su potencial ornamental y su gran capacidad para la purificación del aire. Su floración a parte de melífera, tiene cualidades calmantes y emite un penetrante perfume. En la antigua Roma la parte interna de la corteza del tilo era utilizada para la escritura, esta película se denominada “liber”, siendo el origen etimológico de la palabra “libro”.

Tanto el fresno como el tilo son especies que comúnmente se encuentran en alineaciones urbanas. Sin embargo, la disposición actual de los árboles en el entorno urbano es el resultado de un proceso que se inició en la Edad Moderna. El fenómeno tuvo su origen en varios puntos geográficos de Europa, en ocasiones una extensión o evolución de los jardines y espacios verdes pertenecientes a las élites. Los árboles fueron una herramienta clave para la escenificación del poder y generalmente su presencia era consecuencia del esplendor económico.

La próspera Holanda del barroco creó un modelo de ciudad que los foráneos describían como “un bosque en la ciudad o una ciudad en el bosque”, una imagen que se convertiría en la sensación y referente para el resto de las ciudades europeas. En este caso, el recurso técnico con el que iban ganando territorios al mar acabó creando un concepto de urbanismo. En este proceso los árboles jugaban un papel fundamental, mientras los molinos de viento drenaban el agua, los canales se estabilizaban gracias a la plantación de tilos, olmos y alisos, ayudando a asentar la tierra. La red de canales en ciudades como Ámsterdam eran las principales vías de comunicación y transporte, y generalmente se plantaban árboles a ambos lados de los canales.

Este modelo se generalizó en las ciudades de los Países Bajos siendo el primer ejemplo de un uso práctico del arbolado articulando el espacio público. En el caso de esta circulación por medio de canales, los árboles incluso funcionaban como método de regulación del tráfico, ayudaban a calcular las distancias siendo el precedente de la señalización urbana. Paralelamente es importante destacar cómo en esta sociedad cada vez más próspera, estaba planteando un modelo económico basado en el mercado de valores que posteriormente regiría la economía a nivel mundial. El capitalismo se estaba creando y el modelo de ciudad que proponía incluía a los árboles, es crucial señalar la aparición de la pintura de paisaje como género en este contexto holandés. A día de hoy Holanda es el primer productor mundial de plantas y árboles para cultivo y uso ornamental.

En el siglo XVII, la reina María de Médicis, introdujo en París la costumbre italiana de pasear en carruaje, para esa ociosa práctica se diseñó el “Cours de la Reine”, cuatro alineaciones de árboles de un kilómetro de largo para circular. Lo que en un primer momento estaba destinado a las élites acabo popularizándose, este espacio se convirtió en un lugar para dejarse ver y relacionarse, un lugar para el amor. Este es el primer ejemplo de la conexión entre el arbolado y la circulación de vehículos rodados, las alineaciones arbóreas actuales son una derivación de este pasatiempo.

La revolución industrial fue un nuevo escenario en el que los árboles fueron imprescindibles para hacer habitables las ciudades. En Londres los característicos plátanos de sombra, además de sombra se convirtieron en un modelo de resistencia por su capacidad para la purificación del aire en una ciudad ahogada por el smog.

El momento actual es una evolución de estos precedentes históricos, pero ya no se trata únicamente de resolver cuestiones estéticas o soluciones prácticas a problemas que atañen exclusivamente a las ciudades. La realidad plantea problemas globales que deben ser resueltos de una forma global.

La alineación “El ladrón de miel” funciona como un artefacto de seducción en el que todos los miembros de este ecosistema somos apelados. Son árboles de los que las abejas pueden producir miel, otros animales pueden alimentarse y distribuir las semillas, son una parada para aves de paso, son organismos que purifica el aire, podemos disfrutar de su sombra, pueden dibujar un paseo romántico, podemos beneficiarnos de la miel que producen en simbiosis con las abejas. Solamente falta buscar una simbiosis con los humanos que no sea una mera explotación.

Las ciudades son un árido lugar para el desarrollo de un árbol y la actual crisis climática hace fundamental la presencia de los árboles en el espacio público. Esta relación entre la ciudad y el árbol hace pensar en la búsqueda y el diseño de un urbanismo en el que el beneficio sea mutuo.

En el libro décimo de “Las Metamorfosis” de Ovidio hay una escena en la que al oír la música de Orfeo y su canto al amor, los árboles comienzan a acercarse y junto a ellos las fieras y las aves, quizás, esta escena nos puede servir como modelo para provocar una simbiosis árbol-ciudad, una metamorfosis del urbanismo en el que dejemos de ser meros “ladrones de miel”.

Referenecias:

City Trees. A Historical Geography from the Renaissance through the Nineteenth Century.

Henry W. Lawrence.

University of Virginia Press. 2006

«Trees for streets, empires and paradises: the honey thief» 2023

… and Eros shook my senses like the wind, which in the mountains shakes the oaks…(V, 47)

Sappho of Lesbos

«El ladrón de miel» is part of the project “Arbolado para calles, imperios y paraísos” (Trees for streets, empires and paradises), a series that proposes different models of tree alignments for public spaces. Patterns created from a dialogue between different tree species and the urban context. Conceived as «une allé romamtique», a romantic promenade, it transfers the conceptual programme of a Renaissance or Baroque garden to an urban alignment, taking up the playful character that generally articulated these gardens. «The Honey Thief» is inspired by the mythological figure of Eros, god of love, focusing on desire and love as the driving force and impulse of life. A prototype of this line-up of trees is part of the collection of Artium Museoa, Museum of Contemporary Art of the Basque Country in Vitoria Gasteiz and can be seen installed in the museum square.

The title «The Honey Thief» refers to the bucolic verses of the poet Theocritus in which Eros is stung by bees as he sets out to steal honey from a honeycomb. Weeping, he complains to his mother about how such a small creature can cause so much pain. Aphrodite reproaches him that this is precisely what he does, reminding him of the suffering he causes with the amusement of his arrows. This scene has been widely depicted since antiquity, but it was not until the Renaissance that its subject matter came to the fore in painting. Lucas Cranach and Dürer produced numerous versions, but at this time it took on the moralising connotation of Christianity, an allegory of desire and sin.

The alignment is made up of various species of honey-producing trees, a garden from which the bees can obtain nectar to produce honey. The trees create a scenario where «the honey thief» is represented, showing that it is not only Eros who is “the thief”. The trees are ash (fraxinus ornus), cypress (cupresus sempervires), lime (tilia cordata), fig tree (ficus carica), orange tree (Citrus x sinensis) and apple tree (malus domestica). This line-up is the sum of stories and myths created since antiquity in which trees have been the protagonists. According to the story attributed to Simonides of Ceos, Eros made his bow from ash wood and his arrows from cypress wood. These two trees start from a mythological forest and articulate the alignment functioning as multidirectional vectors, a metaphor for the arrows of Eros.

Mythological narratives are generally stories of love, passion, games of seduction, betrayal, revenge, violence, tragedy… in many cases they are the explanation or mitological interpretation of the creation of many of the plant and animal species and the formation of natural phenomena….

A parallel can be drawn between these games of seduction and the pollination and reproduction strategies of plants and trees. The example of the orchid Ophrys apifera illustrates how a flower has metamorphosed its appearance into the body of a female bee, ready to be pollinated while the male tries to copulate. We find this type of deception and strategy in numerous mythological stories in which divinities transform their appearance into animals, plants, rain, clouds. Trees use multiple tactics to make use of wind, fire, all kinds of animals such as insects, birds, mammals, microorganisms, humans,… these are the resources they use to reproduce and have shaped their evolution. In this landscape formed by multiple interactions we find the relationships of symbiosis, mutualism, predation and parasitism that make up the natural ecosystem.

«El ladrón de miel» transfers this mythological landscape to the urban ecosystem to question the relationship between trees and the city, highlighting the benefits they generate and questioning the imbalances that current urban planning produces. It is a metaphor that underlines our attitude closer to predation and parasitism than to symbiosis where each agent that composes it benefits. It seeks to underline the relationship between species in order to think of a possible mutualism between trees and urban space; it imagines a tree-city mutualism in which we are not mere «honey thieves». This possible symbiotic relationship between the city and the tree encompasses all the agents involved in the process.

Just as the bee causes the metamorphosis of the orchid, trees can transform the physiognomy of the urban space. Nowadays, trees make cities habitable and are essential in their design, they absorb CO2, purify the air, balance the temperature, are the habitat of many species of animals, increasing biodiversity and, globally, are a key element in the fight against the climate crisis.

The link between humans and trees has been inseparable since the origins of civilisations, all cultures have depended on them for their birth and evolution, in fact our existence is not possible without them. The beginnings of agriculture in the Fertile Crescent led to the cultivation and reproduction of fruit trees, which led to the evolution of seasonal settlements to permanent settlements. They have been the resource and raw material of civilisations as well as a vehicle to the transcendental. Forests, gardens and paradises have functioned as settings for original narratives. The gardens of antiquity, the medieval «hortus conclusus», the Renaissance and Baroque gardens kept the mythical stories as a conceptual script in their design. The evolution of these green spaces of private use in their origin, were the public parks and the arboreal alignments of the cities. In the West, the appearance of trees in public spaces, as we can find them today, has a parallel with the development of capitalism and the industrial revolution.

The alignment of trees the «honey thief» functions in the city as an artifact of seduction, it crosses the atrium of the Artium Museum emitting the perfume of flowering, a fragrance that appeals to all the beings that make up the urban ecosystem.

The work superimposes on everyday life the mythological plane created by the narratives in which the trees are the protagonists. It constructs a performative script in which we will be surrounded by numerous characters and we will begin to interact with nymphs, dragons and centaurs, a theatre that appeals to participation. If the trees introduce us to this imaginary landscape, the animals of the urban space also join the multiple stories with their mythological similes. A dog passing by the cypress tree could be Cancerberus protecting the kingdom of Hades, in a fluttering butterfly we could see Psyche trying to enter the underworld, a dove in the square would remind us of the nymph Peristera transformed by Eros into a dove, the nocturnal Miniades would be the bats and owls, Arachne would weave her web among the orange blossoms, a cat would be Galantis, perhaps a rat looking for fruit would be Arimanius, the frogs Latona and the bees protagonists of «The Honey Thief» would have the protective character of Melissa.

The cypress has always had spiritual connotations related to the underworld, being consecrated to the god Hades, its vertical bearing identifies it as a connection between heaven and earth, a symbolic bridge to spirituality. On its more practical side, this tree has been fundamental for construction throughout history. Its upright form makes it visible from a distance, which is why the Romans used to place it along roads in order to trace the course of the roads from a great distance. At the time of the Christian pilgrimages, the cypress also functioned as a signpost, a visual resource in the landscape that provided information from a distance about the possibility of finding water, food or lodging. Depending on the number of cypress trees next to a building, the services were announced to passers-by. I have used this resource in the alignment as the main entrance to the Artium coincides with the way of the «Camino de Santiago de Compostela» through the street «cantón de San Francisco Javier». The cypress tree announces to the «pilgrims» the presence of the Artium, a sensorial or intellectual supply… depending on the visitor’s gaze.

At the entrance to the Artium we are greeted by the fig tree, considered to be one of the first trees domesticated by mankind in the Fertile Crescent. In its mythological version, it was the gift that Demeter, goddess of agriculture, gave to Phytales in gratitude for his hospitality when she was desperately searching for his daughter Persephone, who had been kidnapped by Hades. Mythical accounts of the fig tree also take us back to the Judeo-Christian tradition, to the paradise from which humans were expelled using the fig leaf to cover their nakedness. In turn, it is present in the founding myth of Rome, Ficus ruminalis is the fig tree under which the she-wolf suckled Romulus and Remus.

This tree is a good example of mutualism between two species, the morphology of the fig and its pollinator have co-evolved in such a way that the fig tree is exclusively pollinated by the fig wasp, Blastophaga psenes. On the other hand, the so-called parthenocarpic mutation gives the possibility of reproducing the fig tree vegetatively without the need for pollination, these being the most widespread varieties at present.

As we enter the atrium we perceive the scent of orange blossoms, located inside the Artium alluding to the «Garden of the Hesperides». In one of his labours, Herakles has to steal the «golden apples» protected by the Hesperides nymphs and the dragon Ladon. There are different opinions on whether the trees were really apple or orange trees, I have included both in the line-up because of the climatology and because both are examples of industrially produced fruit species, as Henry Thoreau would point out in «Wild Apples», a whole list of wild species and non-commercialised species that tend to disappear in the face of the exclusive use of certain fruits within a globalised market. Both the orange and the apple are the best example of the productive standardisation of a tree to the detriment of biodiversity. Thoreau imagined beautiful species such as apples that are left on the tree to be stolen by children who jump over the wall. This idea is also present in the «honey thief» the golden apples must be stolen but you will have to avoid being caught by the Hesperides or the dragon Ladon. If you manage to escape, you will have to meet the Sychophants, the informers and guardians of the sacred fig trees, on your way out.

The flowering of the ash tree fraxinus ornus is exuberant in shape and aroma. When incisions are made in the bark, its sap produces a sweet whitish substance that is called «manna» because of its resemblance to the description of the biblical food. In Basque culture, the ash tree has always had a divine character due to the belief in its protective qualities against lightning. Hesiod’s Theogony describes the Meliades, the ash tree nymphs, a name that shares an etymological root with «melífera» which produces honey, and according to the poet Callimachus they were important because they were the protectors of the god of lightning, Zeus, when he was a newborn and his father Cronus was looking for him to devour him. Another version narrates that it was Melissa and her sisters who protected him and fed him with milk and honey. As punishment Cronus transformed Melissa into a worm but later Zeus turned them into a bee.

While Cronus was looking for Zeus, he met the oceanid Philira, to seduce her he transformed himself into a horse and from this union was born the centaur Chiron, the figure of the master healer. Philira, horrified by the creature she had given birth to, asked to be transformed into a tree, the lime tree. Tilia cordata is one of the most widely used trees in public spaces throughout history due to the shade it produces, its ornamental potential and its great capacity to purify the air. Its flowering, apart from being melliferous, has calming qualities and emits a penetrating perfume. In ancient Rome the inner part of the bark of the lime tree was used for writing, this film was called «liber», being the etymological origin of the word «book».

Both ash and lime are species commonly found in urban alignments. However, the current arrangement of trees in the urban environment is the result of a process that began in the Modern Age. The phenomenon originated in various geographical locations in Europe, sometimes an extension or evolution of the gardens and green spaces belonging to the elites. Trees were a key tool for the staging of power and their presence was generally a consequence of economic splendour.

The prosperous Netherlands of the Baroque period created a model of a city that outsiders described as «a forest in the city or a city in the forest», an image that would become the sensation and benchmark for the rest of European cities. In this case, the technical resource with which they were gaining territory from the sea ended up creating a concept of urbanism. Trees played a fundamental role in this process: while the windmills drained the water, the canals were stabilised thanks to the planting of lime, elm and alder trees, helping to settle the land. The network of canals in cities such as Amsterdam were the main routes of communication and transport, and trees were generally planted on both sides of the canals.

This model became widespread in the cities of the Netherlands and was the first example of a practical use of trees to articulate public space. In the case of this circulation by means of canals, the trees even functioned as a method of traffic regulation, helping to calculate distances and being the forerunner of urban signposting. At the same time, it is important to note that in this increasingly prosperous society, an economic model was emerging based on the stock market, which would later govern the world economy. Capitalism was being created and the model of the city it proposed included trees, and it is crucial to note the emergence of landscape painting as a genre in this Dutch context. Today Holland is the world’s leading producer of plants and trees for cultivation and ornamental use.

In the 17th century, Queen Marie de Medici introduced the Italian custom of carriage rides to Paris, and the «Cours de la Reine» was designed for this idle practice, four kilometre-long rows of trees to circulate around. What was at first intended for the elite became popular, this space became a place to be seen and to socialise, a place for love. This is the first example of the connection between trees and the circulation of vehicles, and today’s tree rows are a derivation of this pastime.

The industrial revolution was a new scenario in which trees were essential to make cities habitable. In London, the characteristic shade plane trees, as well as providing shade, became a model of resilience for their ability to purify the air in a city choked by smog.

The current moment is an evolution of these historical precedents, but it is no longer just a question of resolving aesthetic issues or practical solutions to problems that concern only cities. Reality poses global problems that must be solved in a global way.

The line-up «The Honey Thief» functions as a seduction device in which all members of this ecosystem are appealed to. They are trees from which bees can produce honey, other animals can feed and distribute the seeds, they are a stopover for passing birds, they are organisms that purify the air, we can enjoy their shade, they can draw a romantic walk, we can benefit from the honey they produce in symbiosis with the bees. We only need to look for a symbiosis with humans that is not merely exploitative.

Cities are an arid place for the development of a tree and the current climate crisis makes the presence of trees in the public space essential. This relationship between the city and the tree makes us think about the search for and design of an urbanism in which the benefits are mutual.

In the tenth book of «The Metamorphoses» by Ovidio there is a scene in which, on hearing the music of Orpheus and his «song of love», the trees begin to approach and, together with them, the wild beasts and birds. Perhaps this scene can serve as a model to provoke a tree-city symbiosis, a metamorphosis of urban planning in which we cease to be mere «honey thieves».

Referenecias:

City Trees. A Historical Geography from the Renaissance through the Nineteenth Century.

Henry W. Lawrence.

University of Virginia Press. 2006