"front lawn".

Investigando sobre la historia del edificio de la Oficina de Cultura de la Embajada de España, encontré una fotografía de la residencia en las últimas fases de su construcción, con el cartel de la empresa constructora en la fachada y el césped delantero ya instalado, no existía la actual verja del jardín. Este edificio de principio de siglo XX ya incluía uno de los principales elementos en el urbanismo americano que acabaría asentándose por todo el país, el césped delantero.

Los parques públicos y espacios verdes se extienden a lo largo del espacio urbano para conectar con los espacios privados residenciales sin ningún tipo de valla delimitadora. El front lawn es una herencia paisajística del origen colonial inglés de EEUU. Durante el siglo XX, esta práctica se convirtió en una convención identitaria de la nación, un símbolo de lo comunitariamente normativo. Derivó en una uniformización paisajística del espacio urbano a lo largo de los diferentes territorios americanos, con independencia de los diversos climas. La popularización del golf y el éxito del “American way of life” hicieron que este manto verde se extendiera internacionalmente.

Mantener un perfecto césped propició el desarrollo de una gran industria que incluía la comercialización de máquinas cortacésped, sistemas de riego, fertilizantes, herbicidas, pesticidas y producción de semillas. Las zonas norte del país requerían un tipo de hierba completamente diferente a las zonas desérticas, aunque la imagen final fuera la misma.

Los mensajes publicitarios fusionaron el mantenimiento del césped con las cualidades del buen ciudadano, “cuidar tu propio césped es un servicio comunitario”. Una imagen del espacio público que se construía en común, un símbolo de orden, un césped mal cuidado siempre podría ser sospechoso.

En realidad, mantener esa alfombra verde requiere grandes cantidades de agua y productos químicos para luchar contra malas hierbas y todo tipo de animales, una batalla constante contra la biodiversidad. La escorrentía hace que muchos de estos químicos se filtren en las redes fluviales y acaben contaminando ríos, lagos y mares.

Cuestionando su insostenibilidad, el escritor Michael Pollan propuso en 1991, en un artículo del New York Times, transformar el césped de la Casa Blanca en una pradera, un huerto, un humedal o en un huerto de frutales para rememorar como pudo ser el paisaje anteriormente y dar un giro al paradigma.

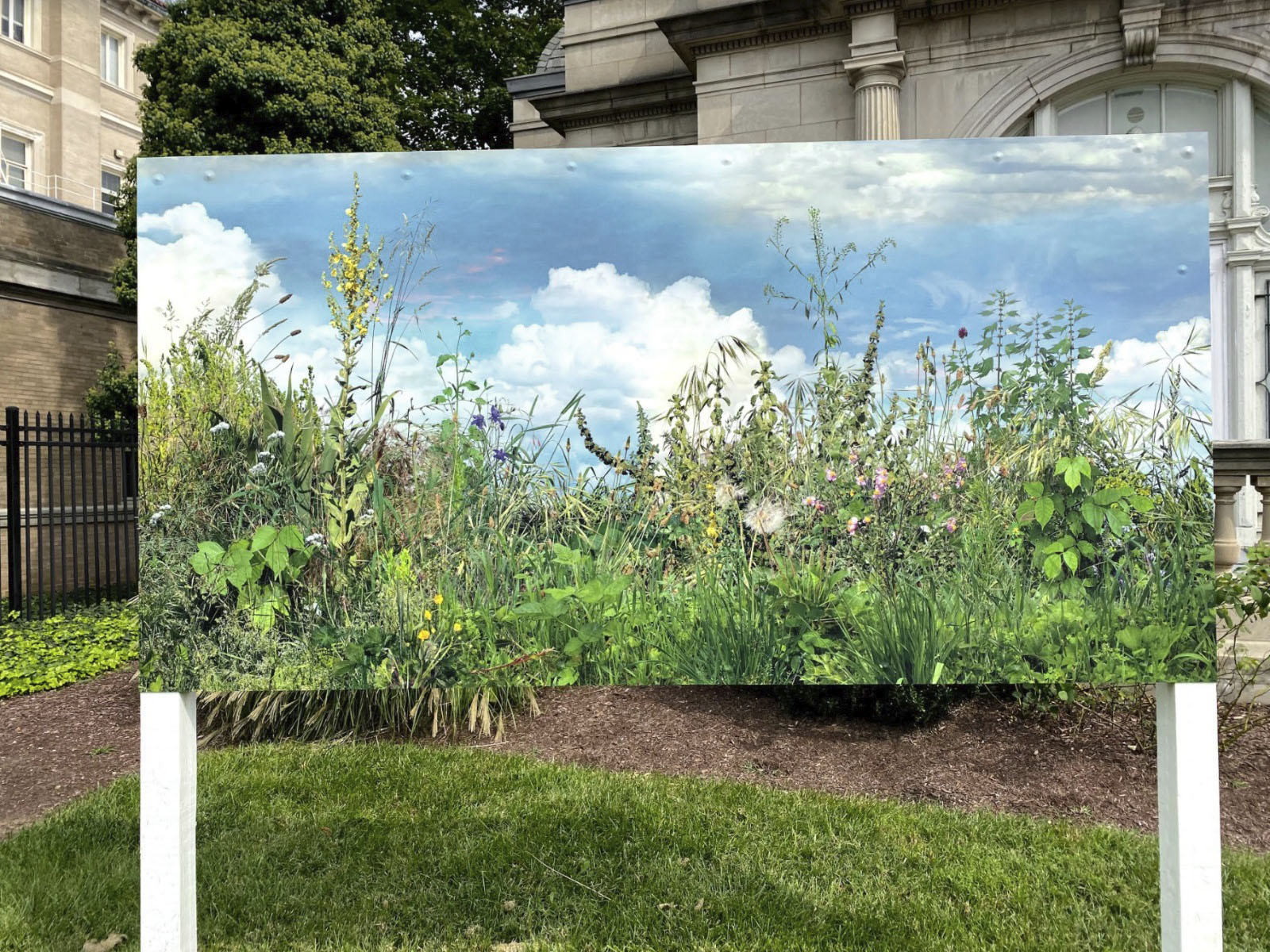

La intervención “Front Lawn” para la Oficina de Cultura de la Embajada de España en Washington, funciona como una valla publicitaria con la imagen de un jardín, antítesis del césped sobre el que está instalada. La planta “poison ivy”, autóctona de los EEUU, invade de forma amenazante el terreno acompañada de otras “malas hierbas”. La escena crea una conexión con el imaginario de DC comics, donde Poisson Ivy, deja de ser la villana botánica para considerarse una ecoactivista.

“Front Lawn”

While researching the history of the Cultural Office of the Spanish Embassy, I found a photograph of the building in its final stages of construction. The photograph depicts the construction company’s sign hanging on the facade and a grass lawn already planted, a garden fence had not yet been installed. This early twentieth century building already exhibited one of the main elements in American urbanism that would end up spreading throughout the country, the front lawn.

The front lawn is a landscaping heritage that came from the English colonial origin of the USA. During the 20th century, this practice became an identity convention of the nation, a symbol of the communal normative. It resulted in a landscape uniformity of the urban space throughout the different American territories, regardless of the different climates. The northern parts of the country required a completely different type of grass than the desert areas, even though the final image of the lawn was the same. The popularization of golf and the success of the "American way of life" caused this green mantle to spread internationally. Today, we see public parks and green spaces extending throughout urban spaces, connected to private residential yards without any type of boundary fence.

As an image of public space that was built in common and a symbol of order, a poorly maintained lawn could always be suspect. Indeed, advertisements fused lawn maintenance with the qualities of good citizenship, sending the message that "taking care of your own lawn is a community service." The emphasis on maintaining a perfect lawn led to the development of a large industry that included the commercialization of lawn mowers, irrigation systems, fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides and seed production.

In reality, maintaining these green carpets requires large amounts of water and the use of toxic chemicals to fight off weeds and protect lawns from a myriad of animals. Runoff causes many of these chemicals to seep into river networks and end up polluting rivers, lakes and seas. A constant battle exists between the traditional lawn and biodiversity. Questioning the sustainability of these lawns, writer Michael Pollan wrote a 1991 New York Times article that proposed transforming the White House lawn into a meadow, an orchard, a wetland or a fruit orchard to recall what the landscape might have been like in the past and turn the paradigm on its head.

The intervention "Front Lawn" for the Cultural Office of the Spanish Embassy in Washington, works as a billboard, presenting the image of a garden as the antithesis of the lawn on which it is installed. The "poison ivy" plant, native to the U.S., is accompanied by other “weeds'' threatening to invade the grounds of the embassy. The scene creates a connection with the imagery of DC Comics, as the caracter of Poisson Ivy is no longer considered a botanical villain but an eco-activist.